Bergen Assembly 2025: Can We Unlearn the Spectacle?

Door Isabel Van Bos, op Sat Nov 15 2025 10:33:00 GMT+0000Large-scale art biennials are everywhere – spectacular, exhausting, inevitable. Bergen Assembly 2025 attempts something different. Under the modest title across, with, nearby, its organizers deliberately turn away from spectacle. Curator and lecturer Isabel Van Bos visited the fifth edition of this collective, decentralized arts festival in Norway. Her report is both hopeful and critical. As she guides us through participatory art projects scattered across the city, one question persists: can we truly unlearn the logics of spectacle and the art market?

Rain glistens on Bergen’s wooden facades. The fjord exhales mist. Walking through the Norwegian city, quay to quay, courtyard to library, you notice how deliberately Bergen Assembly distances itself from familiar biennial codes. No flags turning the city into a marketing campaign, no spectacular announcements demanding attention. Only discreet program booklets guiding visitors through the city, searching for locations that don’t immediately reveal themselves.

This modesty is programmatic. For the fifth edition, organizers Ravi Agarwal, Adania Shibli, and the Bergen School of Architecture (BAS) chose across, with, nearby – typographically modest, rendered in lowercase, promising intimacy rather than grandeur. Their motto: ‘bringing together artistic practices and knowledge production in a process of sharing, rather than showing.’ Where large-scale biennials can feel like box-ticking exercises – every medium, every continent, every crisis – Bergen Assembly opts for another path: not spectacle, but attention. Many of the participating artists are unknown, the interventions sometimes small, even fleeting. These choices have a history.

To Biennial or Not to Biennial?

Fifteen years ago, Bergen posed fundamental questions about the biennial format at the Bergen Biennial Conference (2009). Ironically, the municipality itself had organized the conference while seeking to establish an international biennial of its own. ‘To biennial or not to biennial?’ – the existential question concerned alternatives to the logic of spectacle. The conclusions, compiled in The Biennial Reader (2010), have since become canonical. Bergen Assembly emerged from that self-reflection and still carries its legacy.

It’s no coincidence that ‘triennial’ is avoided. Where a triennial suggests entering a predetermined exhibition, ‘assembly’ invites participation in an ongoing process. The term ‘curator’ is replaced with ‘convener’ – literally, someone who brings together. Not the expert who selects and determines, but the host who creates space and enables connections. What Bergen Assembly asks is more radical than it first appears: it invites visitors, artists, and institutions to unlearn their familiar roles. Not consuming but participating. Not looking but engaging. Not checking off but wandering.

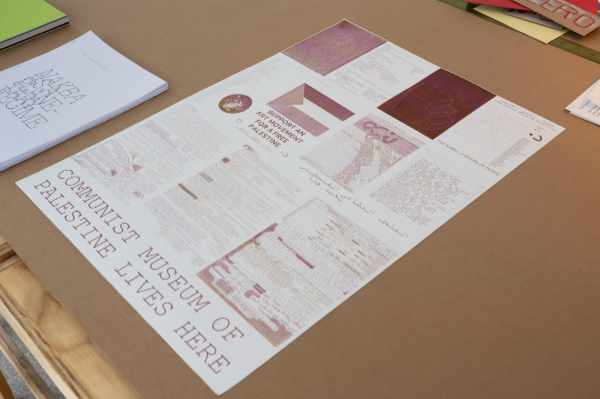

This pedagogical commitment becomes palpable in projects like The Communist Museum of Palestine by Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri. In a mobile studio called P1, people sit in a circle around a table, speaking about power, knowledge, solidarity, and who determines what we know. You have to know where to find these conversations, as their locations are not widely announced.

The Assembly demands a different rhythm: one that resists efficient art consumption. The time you invest resists productivity.

At Bergen Kunsthall, the white exhibition space is transformed. Beneath a colourful shamiana (2025), a traditional Indian fabric canopy by Sanchayan Ghos, a temporary library emerges. This work is part of AgriForum (2021–), an ongoing project that began as an online reading group on agriculture and ecology. The air smells of paper and ink. Stacks of handmade books invite visitors to browse, read aloud, and take notes. The space gestures toward collective thinking, though within a museum context it often remains more symbol than actively used site. More productive are the parallel trajectories in the city: workshops where paper is made from waste and invasive plants. In collaboration with Matskogen Food Forest, participants create a collective zine presented during the Assembly. Projects like these show that Bergen Assembly doesn’t just display knowledge, it produces it.

Bergen Assembly demands a different attitude than the classic biennial visit, where you move from work to work with a map in hand. Here, wandering is the point. Events overlap, locations are scattered, information is fragmented. Some activities are fully booked, others barely announced. The Assembly demands a different rhythm: one that resists efficient art consumption. The time you invest resists productivity. Not everything is designed to be readily consumable, which makes forming judgments difficult. Every visitor experiences a different Assembly.

Bergen as Laboratory: Resistance, Care, and Collective Organization

Bergen Assembly presents itself as hyperlocal. Meaningful city sites acquire new layers of significance. Stranges Stiftelse (1609), originally a poorhouse for women, becomes during across, with, nearby a site for reflecting on social change and community care. Here the exhibition brings together five archives, including Skeivt Arkiv, the Feminist Memory Project, and the Dalit Archive, highlighting strategies of resistance, care, and collective organization.

The historic Gruppe 66, a Bergen-based artist collective from the 1960s, receives a major retrospective at Bergen Kunsthall. By foregrounding archives, the Assembly emphasizes that collectivity is not new but historically rooted in Bergen. Their participatory strategies are reactivated to examine contemporary issues: artists’ working conditions, the necessity of an art academy, the lack of studio space. Their work was deliberately ephemeral – performances, discussion meetings, stencilled texts – to prevent art from hardening into commodities.

Gruppe 66’s work was deliberately ephemeral: performances, discussion meetings, stenciled texts to prevent art from hardening into commodities.

A contemporary example of this local anchoring is the work of Joar Nango, a Sámi architect and artist. Together with filmmaker Ken Are Bongo, he traversed Sápmi – the Sámi homeland extending across Northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia – for the video work Post-Capitalist Architecture TV (2025). They traveled in an old van converted into a mobile TV studio, equipped with a wood stove made from melted car doors and a projection screen fashioned from fish stomach. Their programme records unscripted encounters with Sámi craftspeople and activists, where Arctic landscapes, construction sites, and contested areas consistently provide context for questions about ownership, use, and future. At the Bergen School of Architecture (BAS), this nomadic project unfolds across a semicircle of TV screens. Not all monitors work flawlessly, reinforcing the improvised spirit of the work.

In the raw silos of the Bergen School of Architecture, the pedagogical experiment of unlearning takes concrete form. At Agarwal and Shibli’s invitation, BAS acts as a full co-convener. Under ‘Open Form,’ Assembly themes – knowledge sharing, process-based working, collectivity, planetary consciousness – weave into the curriculum. Teachers develop new courses in which students actively practice these principles. Silos and halls become laboratories for collective making and thinking.

What emerges isn’t harmony but a choreography of collaboration and friction, where individual expertise dissolves into collective action.

Koki Tanaka’s films, shown at the school, reveal this poetic tension. In A Piano Played by Five Pianists at Once and A Pottery Produced by Five Potters at Once (2013-2025), tasks unfold that are, in fact, impossible to carry out collectively. You can’t play one piano with five people. And yet it happens. What emerges is not harmony but a choreography of collaboration and friction, where individual expertise dissolves into collective action. Since 2011, Tanaka has considered himself a facilitator of temporary micro-societies. At BAS, his experiments are not merely displayed but replicated and examined by students. Unlearning becomes a pedagogical practice that fundamentally influences education. In these controlled experiments, Tanaka realizes what the entire Assembly strives for: a temporary community where individual skills serve collective creation.

The Participation Paradox

However, Bergen Assembly struggles with the same pitfalls as other ‘alternative’ exhibitions of international scale. The emphasis on ‘sharing rather than showing’ recalls Documenta 15’s lumbung concept: an Indonesian model of collective sharing and management, named after communal rice barns. That edition drew criticism because the abundance of collectives, archives, and events made the exhibition inaccessible to many visitors. Questions arose about whether artists from the Global South were being instrumentalized, deployed as symbols of authenticity within a Western biennial circuit. Curator-theorist Claire Bishop warned in Artificial Hells (2012) about this romanticization of participation: Who actually participates? Who remains excluded? What power structures lurk behind inclusion rhetoric?

Who actually participates, who remains excluded, what power structures lurk behind inclusion rhetoric?

This tension is palpable in Bergen too. The Maasai Mbili Artist Collective does valuable community work in Kibera’s slums, not just artistically but psychosocially. After Kenya’s 2007–2008 post-electoral violence, they organized art workshops for traumatized children and painted over burned buildings. In Bergen, at Entrée, they present Maasai Mbili Republic (2025): artworks pop up everywhere – against walls, stacked on floors – and visitors are invited to touch and move them. Yet the collective’s real impact lies in Kibera, where their studio functions as neutral ground in an environment marked by violence, poverty, and absent mental healthcare. For artists from such precarious contexts, participating in the international circuit is also an economic necessity. This heightens the risk of instrumentalization in a city that is largely white, affluent, and highly educated, however carefully the Assembly is designed.

There is, however, a crucial difference between Bergen Assembly and Documenta 15, though. As art critic Skye Arundhati Thomas noted in e-flux, many Global South collectives emerge from necessity, responding to absent social infrastructure and authoritarian structures. It is important to distinguish between Western curators who appropriate collective practices as aesthetic strategies and initiatives led by Global South curators themselves, for whom collectivity is not a concept but a survival mechanism.

Agarwal and Shibli are not curators by training. Ravi Agarwal is artist and environmental activist; Adania Shibli a writer and essayist known for reflections on violence, language, and representation in Palestinian contexts. For Agarwal, knowledge-sharing and collective action intertwine with decades of environmental activism in India; for Shibli, with writing about shared traumas and colonized histories. Their curatorial choices do not arise from Western desires for authenticity, but from working methods they have long cultivated: approaching art not as an object but as an instrument for collective reflection and resistance.

Unlearning: For Whom?

Bergen Assembly 2025 reveals the tension between ambition and reality. The conveners have consistently sought to avoid spectacle and instead embrace process-based, relational approaches. By focusing on local sites and knowledge systems, the exhibition remains thematically coherent and intellectually ambitious.

At the same time, it demonstrates how difficult genuinely inclusive alternatives remain within existing institutional frameworks. The intention to share power often collides with the realities of time pressure, funding constraints and ingrained hierarchies that inadvertently reproduce inequalities. Even projects oriented toward participation rely on structures that shape access and visibility, making the conditions of participation unequal.

The intention to share power collides with realities of time pressure, funding, and hierarchies that often unconsciously reproduce inequalities.

Unlearning requires more than goodwill: it presupposes sustained engagement, patience, and a willingness to temporarily relinquish expertise or authority – luxuries not everyone can afford. Such time-intensive, non-productive processes are especially difficult for those working under performance pressure or financial uncertainty, carrying care responsibilities, or living in precarious conditions. Many artists and students find themselves in precisely this situation. This tension intensifies in the context of Bergen Assembly, situated in a city that is largely white, affluent, and highly educated.

Representing Global South and Sámi perspectives thus often remains symbolic: present in discourse and exhibition space, but far less in practice or audience. Local residents or communities for whom Bergen’s featured sites hold meaning are seldom actually involved in the process. The Assembly’s physical proximity alone does not make these places socially, culturally, or economically accessible.

The key may lie in collaboration with the Bergen School of Architecture (BAS). There, across, with, nearby is not merely discussed and theorized, but structurally embedded: students practice unlearning not as a one-off experiment but as an essential part of their education. across, with, nearby becomes powerful when it reaches beyond the exhibition’s timeframe, sustainably anchoring new forms of learning.

Moving beyond spectacle requires more than refined terminology or good intentions. It demands new forms of institutional organization radical enough to repeatedly question their own premises. Can we unlearn ourselves? Bergen Assembly shows that this is possible only within frameworks that facilitate unlearning as an ongoing process, not for those travelling from biennial to biennial, but for those actually living, learning, and working in these contexts.

Read the Dutch original text here.