The artistic director with the crowbar

Door Evelyne Coussens, op Mon Oct 12 2020 07:49:00 GMT+0000The International Theatre Festival of the 48th Biennale di Venezia closed its doors with the award, by an international jury, to the young director Leonardo Manzan. The award and the jury as such were the last exploits of outgoing artistic director Antonio Latella, who has done his utmost over the past four years to break open not only the Biennial but also the Italian theatre landscape. As a jury member, I witnessed Latella’s sometimes paradoxical struggle, which again teaches us that institutional change is no walk in the park – also not in Italy.

It’s easy to spot him, the festival director - at least in this Italian context where a certain vestigial cachet still claims its rights. In Berlin, a festival director wearing slippers is no longer remarkable. In Venice, it is. But Antonio Latella doesn’t only draw attention with his gray beard, earring and informal clothing. The programme that he rolled out over the past four years also turned out to be highly remarkable for the Biennale di Venezia’s theatre section.

Latella (°1967), considered in Italy as one of the greatest directors of his generation, primarily works abroad - he currently has ongoing projects in Vienna and Berlin. In his own country, his group Stabile Mobile (a pun meaning ‘steadfastly fluid’) works without subsidies. Rather than a director or artistic director, he sees himself as a pedagogue, a task he takes very, very seriously -- far past the limits of his classes in various theatre colleges.

Latella asked young and unknown directors to make a new production around the theme of censorship. A programme bursting with artistic risk.

When he was asked to be the director of the International Theatre Festival four years ago – according to him without political support — he had his pedagogical project fresh in his head. It consisted of changing the festival from a showcase of big international names into a platform for encounters and talent scouting. In the first three years, he brought names like Gisèle Vienne and Jetse Batelaan, little known in Italy, to Venice to introduce these ‘free spirits’ to the Italian sector. In 2020, he made the opposite move: Latella filled the programme of the International Theatre Festival with exclusively Italian names - that had never been shown before. Under the title Nascondi(no) (something along the lines of ‘don’t hide’), he asked his mostly young and unknown directors to make a new production around the theme of censorship. In short, a programme bursting with artistic risk.

The past two weeks, together with three colleagues, I was allowed to witness the fruits of Latella’s demarche. I was curious about the quality of the productions, but also about the results of Latella’s attempt, on the one hand to break the festival open for a new generation of directors, and on the other hand to convince the underlying theater landscape to change course in the same direction. Has the artistic director with the crowbar truly been able to put something into motion?

Great Directors

To understand that question, the Italian theatre system perhaps deserves some explanation. Roughly sketched, it consists of a layer of teatri stabili - regional theatres that serve as producers and independently choose a director, a play and a cast. Freely translated: Big Artistic Directors choose Big Directors who stage Big Plays with Big Stars. Collective practices or more horizontal forms of working are just as absent in these stabili as artists under forty. Latella: ‘The only way to get into a teatro stabile as a young director is to lose your youth.’ The artistic choices within the stabili are safe. Thus, Romeo Castellucci, doubtlessly Italy’s most radical theatre export product, was never staged by a teatro stabile.

Beyond the walls of these stabili ‘blooms’ an ‘OFF’ that on the one hand consists of smaller theaters (the stabili d’innovazione) with very limited financing, and an OFF that gets no financing at all, but survives by its artists combining jobs - mostly in education or in hospitality. These companies perform in flat floor halls, and it is in this circuit that the strongest artistic innovation manifests itself. Latella also drew from this circuit for his farewell festival, with the explicit goal of bringing this generation of hidden artists into the limelight. After all, a boundary separates both circuits, says playwright Federico Bellini: ‘Traditional theatre has built a wall to avoid that a conventional idea of theatre disappears. Antonio wants to bring the young there where the institutions won’t allow them.’

His predecessor filled his programme with a standard list of international guests, Latella takes a more educational approach.

And then there’s still… the Biennial. The Biennale di Venezia, with all its disciplinary sections, has a historical origin that, like other festivals, is rooted in a smart entrepreneurial idea that mixes art and tourism. While the first edition in 1895 still promised parties, fireworks and spectacle, the organisation has been able to wrestle itself out of that provincialism throughout its history. With a little help from Mussolini, it tore itself loose from the local government to take a more international course, initially in service of fascism. In the decades that followed, the Biennial was, on multiple occasions, the platform on which art and politics fertilised each other, explains the excellent exhibition Le muse inquiete in the Giardini, because the Biennial has always fought to be the place where ‘it’ happened.

Where does ‘it’ happen?

But since the fall of the Berlin Wall, ‘it’ has been hollowed out to a marketing slogan rather than a true artistic slash political encounter. In the past decades, the programmes of the big European theatre festivals (Avignon, Salzburg, Berlin, Amsterdam…) are interchangeable, with a standard list of international guests: Thomas Ostermeier, Milo Rau, Christoph Marthaler, Jan Lauwers… They come with one top performance and disappear again, en route to the next venue. Latella’s predecessor, the Catalan Àlex Rigoal, also filled his programme mostly in the same way. Although Latella underlines the idea that one’s own work only grows in confrontation with international reference points, he took a different approach. More educational, shall we say.

He broadened horizons in the past few years through a formula in which not one but two to three performances were staged by each international guest, so that the audience and the Italian directors could get to know the work in depth. He also did it by placing the Biennial College at the heart of the festival, the workshop part that gives young artists of all disciplines the chance to work with big names (‘maestri’) from home and abroad. And this past year, he specifically took pedagogical aim at Italian theatre directors and (foreign) programmers by astonishing them with a programme of Italian talent. Latella: ‘I keep shouting that we need to accompany the audience in discovering new languages. That is necessary, because many artistic directors are not aware of those languages themselves.’

The work at the Biennial is painfully short-lived: for the majority of the artists invited, the premiere was also the derniere.

Latella’s plan thus takes a two-part shape: removing the borders between the stabili and the OFF within Italy on the one hand, and between the rather isolated Italian theatre and the rest of Europe on the other hand. It is undeniably too early for a conclusive evaluation of this attempt; the next few years are likely to reveal whether his approach will bear lasting fruits. On top of that, the covid-19 pandemic is no gift: as it does everywhere, it causes a fearful reflex to restore the old certainties. Bellini says that some stabili had just carefully started producing young talent, but that it is unclear whether this opening will last.

Self-censorship

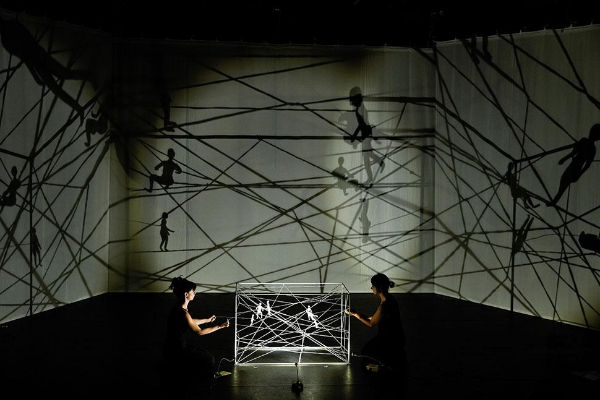

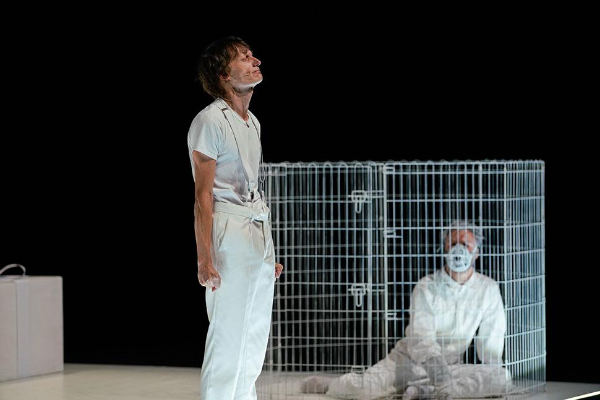

About the festival itself, however, a few remarks can nevertheless be made. The first and most important observation is the quality and diversity of Italian theatre. If Latella’s programme is representative of what is happening in the OFF, the majority of that scene would not be out of place in the programming of our most exciting art centres. Among the 26 performances were a breathtakingly brutal staging of De Sade (Fabio Condemi, La filosofia nel boudoir), flawless puppet theater (UnterWasser, Untold), an ecstatic club experience (Industria Indipendente, Klub Taiga), an insane psychological parable about George Bush (Alessandro Businaro, George II). Not to mention the drag show, the WhatsApp theatre or the 1-on-1 interactive experience. All in one way or another connected to the theme that Latella had ‘imposed’: censorship.

Latella underlined multiple times that he wanted to steer towards creations that, in the first place, would be free of _self-censorshi_p, which he interprets as sales-oriented thinking that inscribes artistic creation within the laws of the market. His directors were challenged to create without thinking about sales or touring - only in that way would their true artistic potential come to light. Siete liberi, siate liberi: you are free, be free. Creating without ulterior commercial motives may lead to fresh and daring theatre, but it is also fated to be painfully short-lived: for the majority of the artists invited, the premiere was also the derniere. That is harsh, because artistic potential doesn’t pay the rent, and it gives Latella’s challenge a somewhat unworldly touch. Latella points out that his ‘capital’ consists of the presence of the prospecting theatre directors, who, however, do not show up in large numbers: fewer than half of the teatri stabili are represented.

What couldn’t be seen, were the themes European theatre is talking so much about: migration, decolonisation, climate change.

The ultimate winner of the international jury prize (to which, by the way, no money is attached) was Glory Wall, a razor-sharp and hilarious installation in which the actors operate from behind a wall via so-called glory holes - holes that guarantee anonymous sex in a dark room. Leonardo Manzan and his team tackle the theme of censorship with a cheerful and self-critical sequence of mini actions in which the inability of theatre to be a political motor is central. A special jury mention went out to the Platonov adaptation of Liv Ferracchiati, who places the powerless women from Chekhov’s drama on the foreground and intervenes himself in the role of ‘Reader’ to portray the essence of this weary protagonist. Ferracchiati wrote a brilliant topical version of the play, acted as a director and also charmed the audience with his exceptional charisma as an actor.

Blind spots

There were also blind spots. What couldn’t be seen, or barely - in a regrettable form of self-censorship - were the themes European theatre is talking so much about: migration, decolonisation, climate change. That is remarkable, especially in the case of the climate issue: imagine that all of these young artists, who knew they would premiere in Venice, don’t mention a word about it - while they were sitting in the front row with the abnormally rising water right underneath their feet. The theme is not alive, according to a somewhat embarrassed Federico Bellini. Not with the theatre makers, but equally not in the public debate. Italy does not have a green party. Moreover, the regional elections that took place during the festival brought Venice the re-election of a right-wing mayor (Luigi Brugnaro), who sees the city as the chicken with the golden eggs - to be slaughtered as soon as possible, even at the cost of the residents’ livability and the ecological destruction of the laguna.

A second sad exercise in counting only produces one black actress in 26 productions, in Daniele Bartolini’s The Right Way, which ironically enough is a play about political correctness. (About the audience, I can be short: 26 plays long, it was unilaterally white.) Bellini argues that ‘there are no black actors’, an argument that has lost all validity in Belgium and neighbouring countries. In Italy, it does seem, however, that the situation must be assessed differently. A Venetian friend explains to me that the political and socio-economic context in which immigrants arrive in Italy is incomparable. Twenty years ago, the Italian parliament, under pressure of the far right, adopted a number of laws making it impossible for newcomers to obtain citizenship. That means that they, but also their children and the children of their children, barely gain access to schooling or decent work, in short: to every possibility of social mobility.

A sad exercise in counting only produces one black actress in 26 productions.

But even that discussion, and the discussion about the absence of people of colour in the arts, is seemingly not taking place in Italy. ‘It’s true’, Bellini admitted, ‘the Italians do not concern themselves with some fundamental issues.’ All the more reason for an artistic director to do so, right? Maybe some of the very young directors that Latella selected for the festival cannot be expected to have the alertness to pointedly think about their cast - or can they? - but an artistic director who labels himself a pedagogue can do so in any case. Latella showed himself to be decisive in many areas, maybe he could have made more efforts to make a statement in that regard as well. If he doesn’t have the power to do so, then who does?

Power and money

That question also touches on a last observation, not directly related to the artistic quality or theme but to the internal organisation of the festival. For an outsider having in mind the Flemish theatre history around the democratisation of work relations, it is surprising how much the culture of the maestri, the Great Individuals, affects even this ‘special’ Biennial. It crystallises from the figure of Latella himself who, despite his goal of collectivity - the theatre Biennial as ‘one big common work of art’ -, does call a lot of the shots. Latella himself made the selection of programmed artists, he himself awards the Golden and Silver Lions, he decides on the winner of the bando, a trajectory that rewards one young director with a production budget of 110,000 euros and a yearlong tutorship - by Latella himself. The question does slightly arise as to whether that setup of collectiveness can withstand the hierarchical power concentration around one person and the competitive reality of award ceremonies and juries.

With just over one million euros, the festival budget looks pale against the budgets of the Festival d'Avignon or the Salzburger Festspiele.

Latella himself strongly relativises his power, by connecting it to the poor financial context in which the International Theatre Festival operates. With a little more than one million euros, the festival looks indeed pale in comparison with the budgets of the Festival d’Avignon or the Salzburger Festspiele. It is almost cynical to say, but it could be the explanation for the fact that a man with such an appetite for destruction manages to push through to this position. In our introductory conversation, Latella pointed out that, in Italy, you can only change something from the inside out, by ‘penetrating an institution and setting off a bomb there’.

With Latella, the Biennial’s board of directors took a calculated risk: it let loose an international name with status on a playing field on which relatively little money circulates, with the assurance that the revolutionary will leave after four years. Furthermore, Latella made no secret in the conversation of the fact that it was four difficult years, and that the organisation is relieved to see him go. Latella: ‘In this last year, I have broken all unwritten rules.’

What’s next?

It is the morning of the award of ‘our’ prize, the prize of the international jury and the special mention. In their word of thanks, both Leonardo Manzan and Liv Ferracchiati underline how much they owe to the trajectory that they’ve taken in the past year. Ferracchiati, in tears: ‘This is the most beautiful thing that has ever happened to me in my life.’ In the little room with a limited number of viewers, Manzan’s parents film the ceremony, gleaming. We, too, are moved: despite all possible critical reservations, on this day we witness the deep joy of two young people who get a special chance, a chance to grow in a system that seemingly isn’t waiting for them. In Latella’s parting words, which he doesn’t see as parting words (‘because the “creative process of life” continues’), he launches a warm call to the theatre directors to take further care of this very promising generation: ‘It is up to you now.’

One thing is sure: in the previous 47 editions, there was never a theatre biennial like this one. Whether the Biennial and the underlying Italian theatre landscape really were receptive to Latella’s attempt to force a break, and whether his maneuver can lead to a genuine turnaround, remains to be seen. In the first place, we wait for the name and profile of his successor - which will indicate the course the organisation will take. At the moment of our departure from Venice, Latella’s successor is not yet known.