The Palestinian 1968: struggles for dignity and solidarity

Door Omar Jabary Salamanca, op Thu May 31 2018 22:00:00 GMT+0000Decentering is an act of displacing from a central position. This essay introduces the figure of solidarity constellations to explore how Palestine became situated in and connected to a vast wave of global struggles against imperialism during the long 1960s and 1970s.

"Anyone who owns a vehicle, including our friend Abu Amar [Yasser Arafat], get in and leave”. According to Haim Bar-Lev, the Israeli Army Chief of Staff, this was one of the leaflet messages airdropped over the Jordanian town of Karameh on the eve of March 21, 1968. (1) Beyond donkeys and some tractors however, few had vehicles in this town.

Karameh, situated along the Jordan River near the Allenby Bridge, was home to a large Palestinian refugee population displaced during the Israeli ethnic cleansing campaign that began in 1948 and continues after 1967. Its strategic location made it into a base for clandestine guerrillas chased off from Palestine during the previous years. From this and other locations along the border operations were launched against the Israeli state in an attempt to revitalize the liberation struggle.

At dawn, clouds of leaflets were followed by a strong Israeli force of around 15,000 troop supported by tanks, artillery and aircraft which after crossing the Jordan river clashed with the Jordanian army and Palestinian guerrillas. On the West Bank side, in the occupied Palestinian town of Jericho, an international crew of journalists invited by an overconfident Moshe Dayan covered the event. The aim of the operation was to capture Arafat and other militants, dead or alive, and level the town.

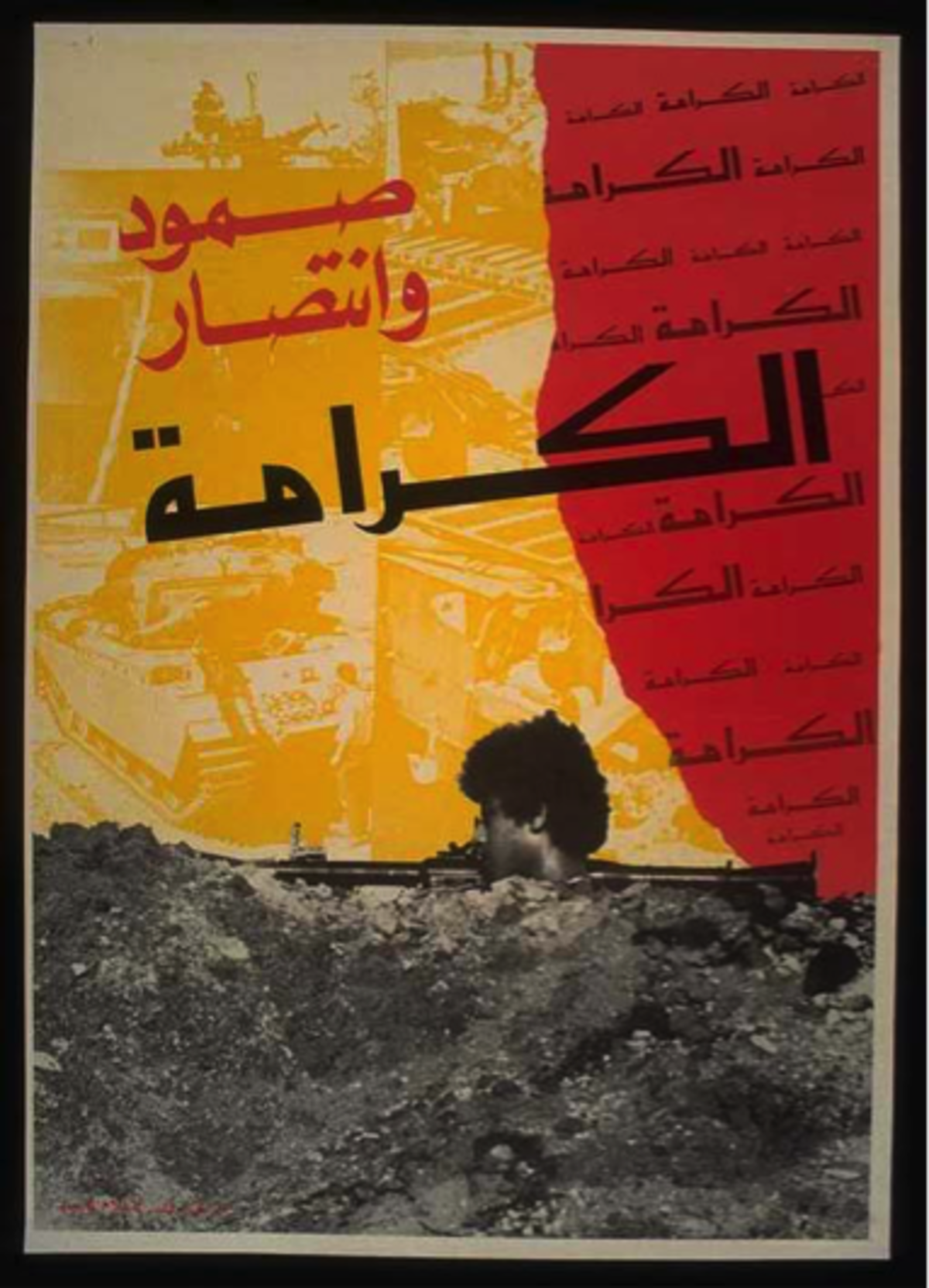

The victory in Karameh (Arabic for dignity) in March 1968 became imprinted in Palestinian collective memory.

The assumption was that Jordanian forces would not actively take part in the battle, as it happened during the June War in 1967 – when in six days Israel occupied the Palestinian West Bank, the Gaza Strip and Jerusalem as well as the Syrian Golan Heights and the Egyptian Sinai.

Along Zionist Ashkenazi veterans from previous settler wars in Palestine, there were household names such as Benjamin Netanyahu, the current Prime Minister of Israel. Bibi, as part of his baptism of fire, was in charge of manning a checkpoint on the outskirts of the town to capture Arafat. There was also Matan Vilnai, then a young paratroop commander and today infamously known for declaring that if Palestinians in Gaza continue to resist they “will bring upon themselves a bigger Shoah (Holocaust)”. (2) The Israeli state and the army are after all a small, big family.

Arab victory

Ill trained and equipped for the battle and against lessons from guerrilla warfare books that Palestinian militants had devoured since the 50s – including the likes of Che Guevara, Mao Zedong, Franz Fanon and Võ Nguyên Giáp – armed factions, namely Fateh, the Palestinian Liberation Front and the Palestinian Liberation Army, decided to take a stand in Karameh and confront the Israeli army and its invincible aura.

The battle of Karameh epitomized a turning point for Palestinians and for the Arab world at large.

During the clash which lasted until the early evening, many were killed and injured and the town destroyed. Palestinians sustained the highest number of loses, with more than a hundred dead, an equal number of wounded and about 60 prisoners taken. Israel declared 28 dead and 90 wounded, and four tanks, various armored vehicles and an aircraft destroyed.

After the humiliating Arab armies’ defeat during the Six-day War, the brave stand at Karameh came to symbolize a much-needed Arab victory. People took the streets to celebrate and observe captured Israeli tanks and armored vehicles paraded in Amman’s Hashimi square. Following the festivities, thousands from all nationalities turned to Palestinian recruitment offices in Jordan, Lebanon and Syria to join the armed struggle.

In spite of Jordanian’s elevated losses and its decisive role in the battle, the victory was instantly and skillfully turned by Palestinians into their own. Fittingly, Karameh (Arabic for dignity) became imprinted in Palestinian collective memory. (3)

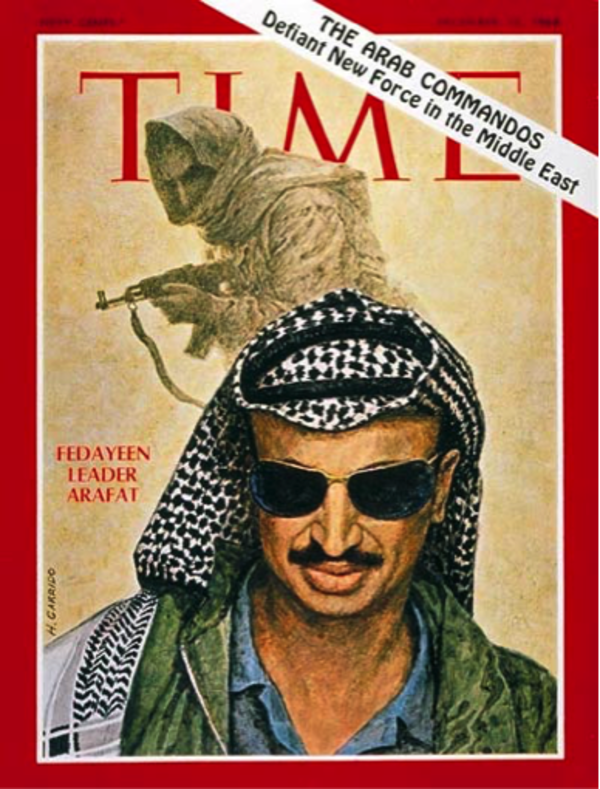

Time magazine immortalized this moment in the cover of its December issue: in front, a colored bust of Arafat with Kufiyah depicted as a modern yet intimidating version of the Gulf Arab man, and, looming in the background, a pale sand-colored fedayeen (freedom fighter) face covered and carrying a Kalashnikov. The orientalist image nevertheless captured the world’s imagination shedding light into Palestinian plight and aspirations. By defeating the Arabs in 1967, Israel revived the Palestinians.

Palestinian Fedayeen

The battle of Karameh epitomized a turning point for Palestinians and for the Arab world at large. Most significantly, Fateh in concert with other factions created a rupture with Arab tutelage over Palestinian national identity and their claims to represent them and their struggle, particularly from the Jordanian and Egyptian states. Only in 1974 the Arab League and the United Nations would recognize the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.

This process irreversibly inserted the aspirations of Palestinians onto the international agenda, no longer as refugees in need of humanitarianism, but rather as fedayeen with claims to Palestinian statehood, self-determination and an inalienable right of return. By organizing and arming their existence, Palestinians reasserted their longstanding struggle over their land and for recognition. In many ways Karameh constituted a moment of forced visibility that interrupted the coherent story of Zionist settlement.

The disruption not only collapsed the continuities of the Nakba and the Naksa, it also brought together a people long time separated. These were the days when Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir would rehearse the mantra that "It was not as if there were a Palestinian people in Palestine and we came and threw them out and took their country away from them. They did not exist." (4)

Palestinians now incarnated the ongoing struggle for Arab self-determination and revolution.

Karameh was also crucial in so far as it precipitated the rise of armed struggle and the emergence of the Palestinian fedayeen. No longer underground, they became a symbol of Arab defiance and bold militancy, the vanguard for national liberation in the Arab World. Palestinians now incarnated the ongoing struggle for Arab self-determination and revolution.

By the early 70s, they filled the void left by Arab national liberation movements which were perceived as having failed and abandoned their socialist aspirations and progressive agendas. Karameh was another stop in the long road for Palestinian liberation, yet it was also a spark that released widespread enthusiasm for insurrection throughout the region.

Solidarity constellations

The story of Karameh and the revolutionary fervor that ensued cannot however be understood in isolation or as a linear sequence of events. Rather it could be read as contingent on a vast constellation of relations and movements, local, regional and transnational, more often than not incommensurable with each other. To be clear, the Palestinian revolutionary movement was an outcome of a multiplicity of ideological projects and contributions shaped by material conditions on the ground and naturally entangled in considerable contradictions. (5)

Perhaps more interesting here is to focus on the ways the star of Palestine became situated in relation to the Third World, a transnational solidarity constellation key to its brightness and one of its essential conditions for possibility. Like the predominant Arab left position of the 1960s and 1970s, many Palestinian mothers, workers, intellectuals, poets, filmmakers, artists and community leaders, understood themselves in a context mediated by Empire, settler colonialism, slavery and the toxic Cold War polarities of the Soviet Union and the United States (US).

Influenced by and aware of regional freedom movements from Algiers to Yemen, their analyses were grounded in a history of struggle against British and French colonialism following the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Experience and practice were the guides informing a political economy that aimed to challenge classed, gendered and raced social orders at once. (6)

Long before 1968, Palestinians already participated and were connected to experiments in planetary solidarity such as the League against Imperialism, established in Brussels in 1927, the Bandung conference in 1955, and the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAL) funded after the Tricontinental conference in Havana in 1966. These were some of the spaces where the wretched of the earth of the 21st century, from Vietnam and Chile to Angola and Algiers, would meet to collectively conspire for a future without colonialism, capitalism, racialism and patriarchy. (7)

Shared experience of dispossession

It did not take long for countries in the Third World to understand Israel as a racist and national settler colonial project structurally integrated in Empire rather than a liberated postcolonial state as it often presents itself. Whatever their position, few honestly doubted that in Palestine the victims of the victims of the Holocaust had been unjustly dispossessed from their lands.

A shared experience of dispossession is what brought diverse cultures and identities together in a struggle for dignity.

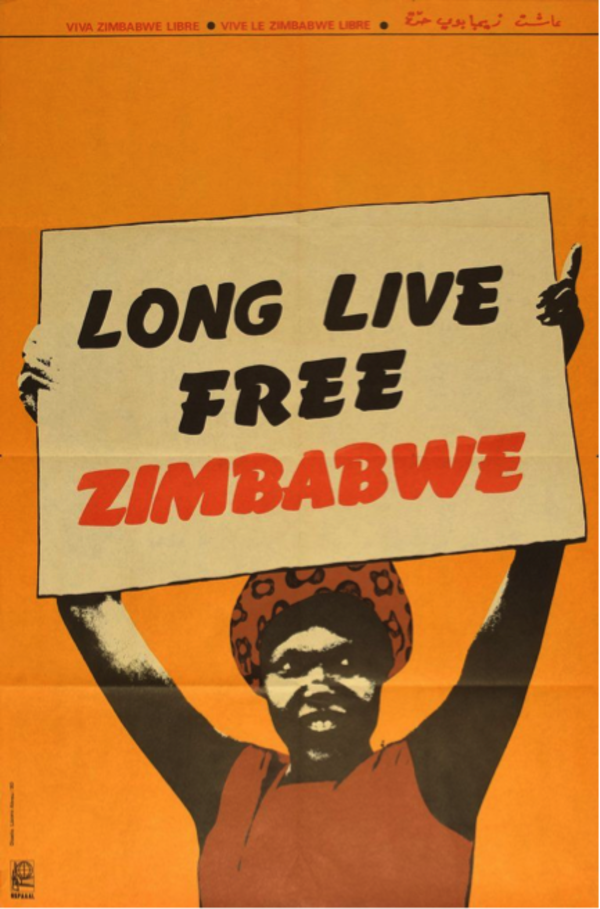

It was however the alliances of the state of Israel with settler regimes like South Africa and Rhodesia and its implication in US and European counter-revolutionary efforts – in disparate places such as the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Zaire, Botswana, El Salvador and Argentina — that made other liberation struggles find common cause with Palestine.

The commitment of intellectuals like Mehdi Ben Barka, a Moroccan revolutionary opposed to King Hassan II and secretary of the Tricontinental conference, were central in making visible these connections in the African context. Ben Barka was a leading voice denouncing Israel’s growing influence in countries like Mali or Tanzania and exposing the miraculous glow of its development achievements and the problematic nature of its investments in the region. Two months before the Tricontinental conference in Havana, in 1965, he disappeared in France allegedly abducted by French police. (8)

It is crucial to recognize that these struggles were historically marked by countless assassinations, disappearances and imprisonments of leaders and militants, women and men, young and old, but also by an urgency to counter the fragmentation of communities, people connections and indigenous knowledges increasingly subsumed in and through the violence of colonial capitalism.

This shared experience of dispossession is what brought diverse cultures and identities together in a struggle for dignity, not as an abstract universal, neither as a right or an entitlement to be obtained from the oppressor but rather dignity as an inherent feature in the lives of people that had to be reaffirmed as an individual and collective duty. (9)

Radical culture of resistance

The manifestations of this global culture of resistance and solidarity took on heterogenous and creative forms – from human and material support as well as exchanges in experiences of community organizing and education to worker union solidarity and cultural production.

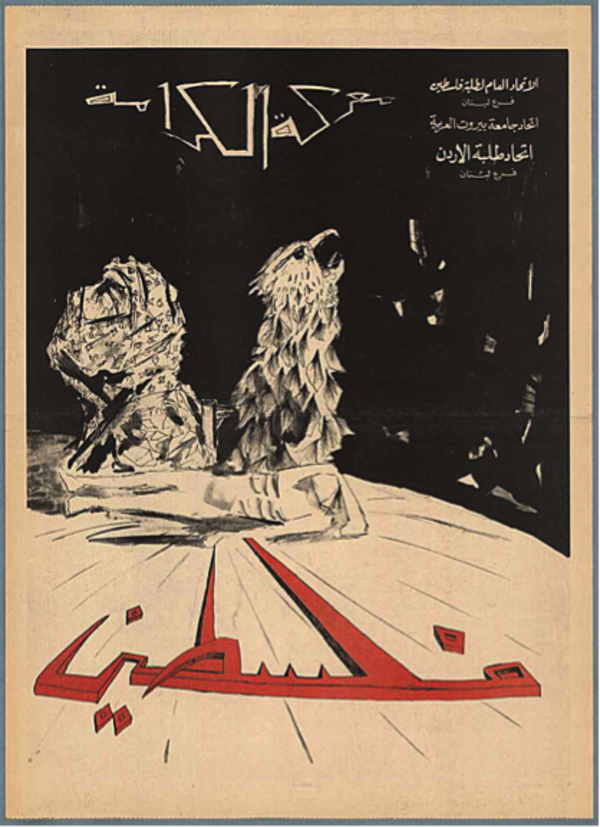

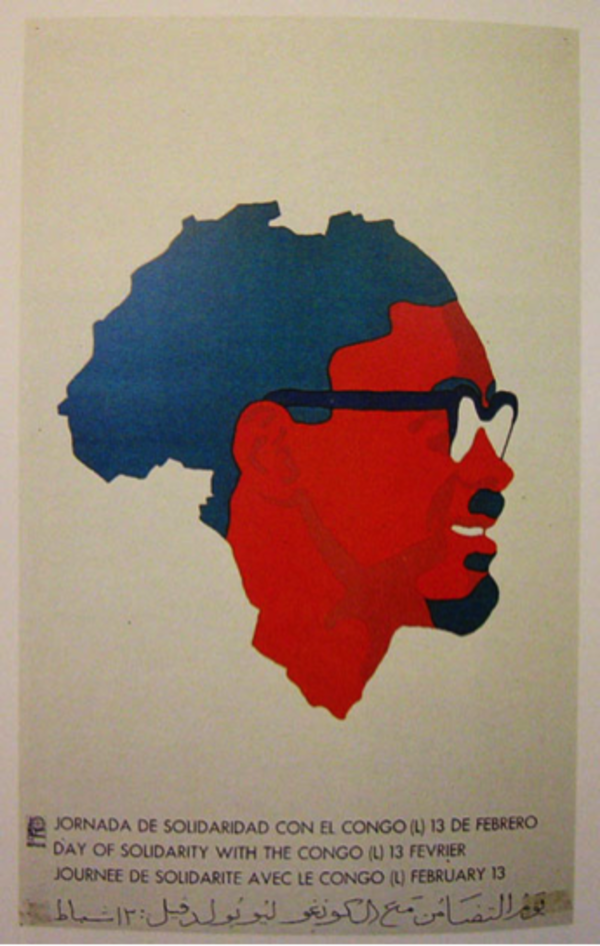

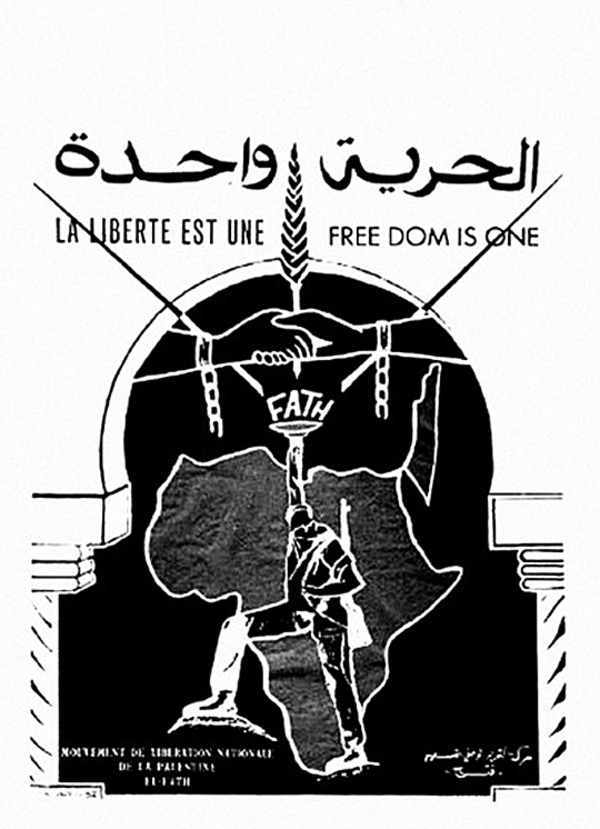

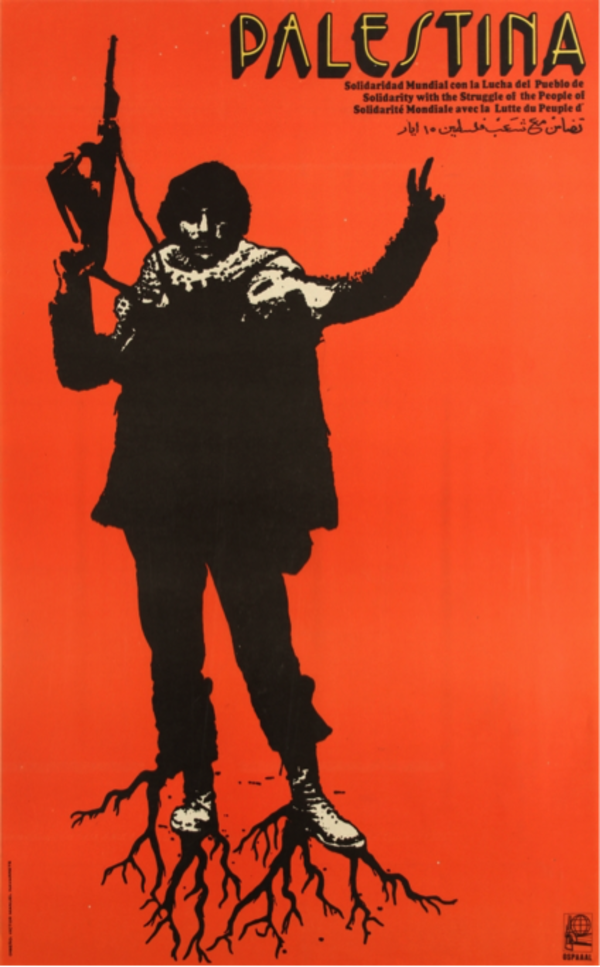

The collection distributed by OSPAAL to 87 countries with the Tri-Continental magazine from the 1960s until the 1990s, is a beautiful visual historical record of this alliance and sense of solidarity. Designed to support liberation and independence movements that swept the world after the Second World War, the posters promoted internationalism across the Third World and included messages written in Spanish, English, French, and Arabic. Most of these posters are as relevant today.

In Palestine, filmmakers like Mustafa Abu Ali, Sulafa Jadallah, Hani Jawhariah and the Palestine Film Unit as well as authors such a Ghassan Kanafani, Mahmood Darwish, Sahar Khalifeh, Emile Habiby and Samih al-Qasim among many others, all were engaged in advancing a radical culture of resistance. This cultural production, as Maha Nassar argues, enabled global solidarities and contributed to deprovincialize and situate Palestine in a transnational comparative framework of anticolonial cultural resistance.

Nassar relates how Arab publications like al-Ittihad and al-Jadid, affiliated to the Israeli Communist Party, would regularly publish translations of Pablo Neruda, Federico Garcia Lorca, Langston Hughes, Nazim Hikmet or texts by contemporary engaged Arab poets from Syria to Sudan. Afro-Arab solidarity around freedom movements was particularly central in the Palestinian struggle, in large part due to Gamal Abdel Nasser’s legacy.

During the 60s, al-Ittihad covered events in the Congo and during the weeks following Patrice Lumumba's assassination it published several editorials blaming his death on imperialist forces, local villainous traitors and those who hide out in Brussels and Washington. (10) As captured in a poster designed by Guy Le Querrec and published by Fatah in 1969, freedom was one from Cape Town to Akka.

Afro-Arab political imaginary

Afro-Arab solidarities and connections forged in the region also extended to diasporic Black liberation struggles in the US. While Qassim translated the prison poetry of Viet Cong leader Ho Chi Minh for the readers of al-Jadid, one of his own poems would end up in a cell in the prison of San Quentin, California, signed and authored by prominent Black Panther activist and writer George Jackson.

Black-Palestinian solidarity was intensively cultivated during the late 1960s at the height of the Black Power movement.

Greg Thomas explains how this literary ‘mistake’ speaks to the resemblance of prisons conditions among those engaged in liberation struggles providing ‘a powerful illustration of kinship in the practice of revolutionary political solidarity’. (11)

Black-Palestinian solidarity was intensively cultivated during the late 1960s at the height of the Black Power movement. Many prominent figures like Malcom X, Stokely Carmichael, Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis, and James Baldwin among others, supported the Palestinian struggle contributing to develop what Alex Lubin calls an Afro-Arab political imaginary. Solidarity is never a given and it only took a bold statement in support of Palestine to expose antagonisms within long established left political coalitions, within the black community but also between Jews and blacks.

In 1967, for instances, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) led by Stokely Carmichael made the decision to issue a statement of support for the self-determination of the Palestinian people. This created a rift that tensed and eventually split the black freedom movement along ideological and solidarity lines.

Divisions notwithstanding, Palestine became central to the black freedom struggle, particularly among a new generation of black nationalist activists who sought political affinities beyond the civil rights paradigm and the nation-state. (12) The revolution was fought with bullets, demonstrations and strikes but also with statements, ideas, posters, books and films.

From Chile to Paris

Solidarity constellations subvert artificial divisions and center-periphery paradigms extending far and wide from East to West and South to North. Depending on where one stands however some stars shine more than others. The role played by the colonized in diasporic and migration contexts beyond the Arab region is often one of those overshadowed features.

Imperial metropoles are that other space that illustrates the central role of colonized and migrant peoples in extending and sustaining solidarity constellations.

A case in point are Palestinians in Chile, the largest community outside the Arab world, which were equally implicated with political realities in their host country as well as developments in the motherland. Emphasizing the particular trajectories of this community, Cecilia Baeza documents the role played by figures such as Juana Dip Muhana, Nancy Lolas Silva, Michel Marzuca, Fuad Dawabe, and Nicola Hadwa in articulating solidarity agendas with worlds not left behind and with their distant but significant Palestinian others. (13)

In this period, Chilean-Palestinians from diverse class backgrounds had to navigate a shifting political context that saw the abrupt end of a revolutionary era with the assassination of Salvador Allende in 1973 and the imposition of a military junta ruled by Augusto Pinochet until 1990. Palestinian industrialist families in Chile largely supported Pinochet while others fought simultaneously against the dictatorship and for the liberation of Palestine. (14)

Imperial metropoles are that other space that illustrates the central role of colonized and migrant peoples in extending and sustaining solidarity constellations. Paris and Marseille are paradigmatic sites of radical organizational forms that exponentially multiplied alliances between Palestinian and migrant workers struggles, politicizing and mobilizing generations to come.

Abdellali Hajjat has drawn attention to how in the aftermath of Black September in 1972, the comités Palestine formed by Arab workers and students largely of Maghrebi descent, together with the Gauche Prolétarienne and with strong support from the PLO sought to politicize Arab workers in France. They did so through an international, anti-imperialist struggle framed in Marxist and Arab nationalist terms. As Hajjat explains, what distinguished the comités Palestine from other organizations is that its militants considered France a site of struggle for migrant workers’ preoccupations rather than for advancing their own national cause back home. (15)

From Chile to Paris, these strategies of resistance were built on a long legacy of political organizing and solidarity. It was this inclusive labor of imagining, creating and experimenting with different constellations of solidarity and cosmological understandings of the world that scared the guardians of Empire and which remains at the core of their ongoing attacks.

La lucha continua, it never ends

Resistance strategies travel long and far but so do tactics of repression. Consider how French counter-insurgency tactics acquired during the Battle of Algiers and the colonization of Algeria ended up informing Pinochet’s vicious policies of torture and repression; the way authoritarian methods targeting anti-colonial movements, migrant workers and popular classes during the long 60s in France shape current political and policing tactics against the indigènes de la République, assumed as security threats and internal enemies; or how the state of Israel has turned a long history of Palestinian repression into a profitable battle-tested commodity exported the world over.

In the Arab world the relative coherence of revolutions of people against regimes has turned into struggles pitting regime against regime and people against people.

These are also part of the perverse legacies of the global 60s. Today an anxious feeling of being in a permanent state of crisis seems to have taken over as we observe an increase in and normalization of inequalities and political repression against the population. This regression is to a large extend eclipsing and undermining the political space and fundamental work of individuals, communities and movements around the world.

The situation is also more complex. In the Arab world the relative coherence of revolutions of people against regimes has turned into struggles pitting regime against regime and people against people. Meanwhile, a long century of Israeli settler colonialism continues to test the endurance of the Palestinian population. In this context, as we move forward, it is important to draw lessons from the contradictions and complexities that shape genealogies of solidarity constellations past and present.

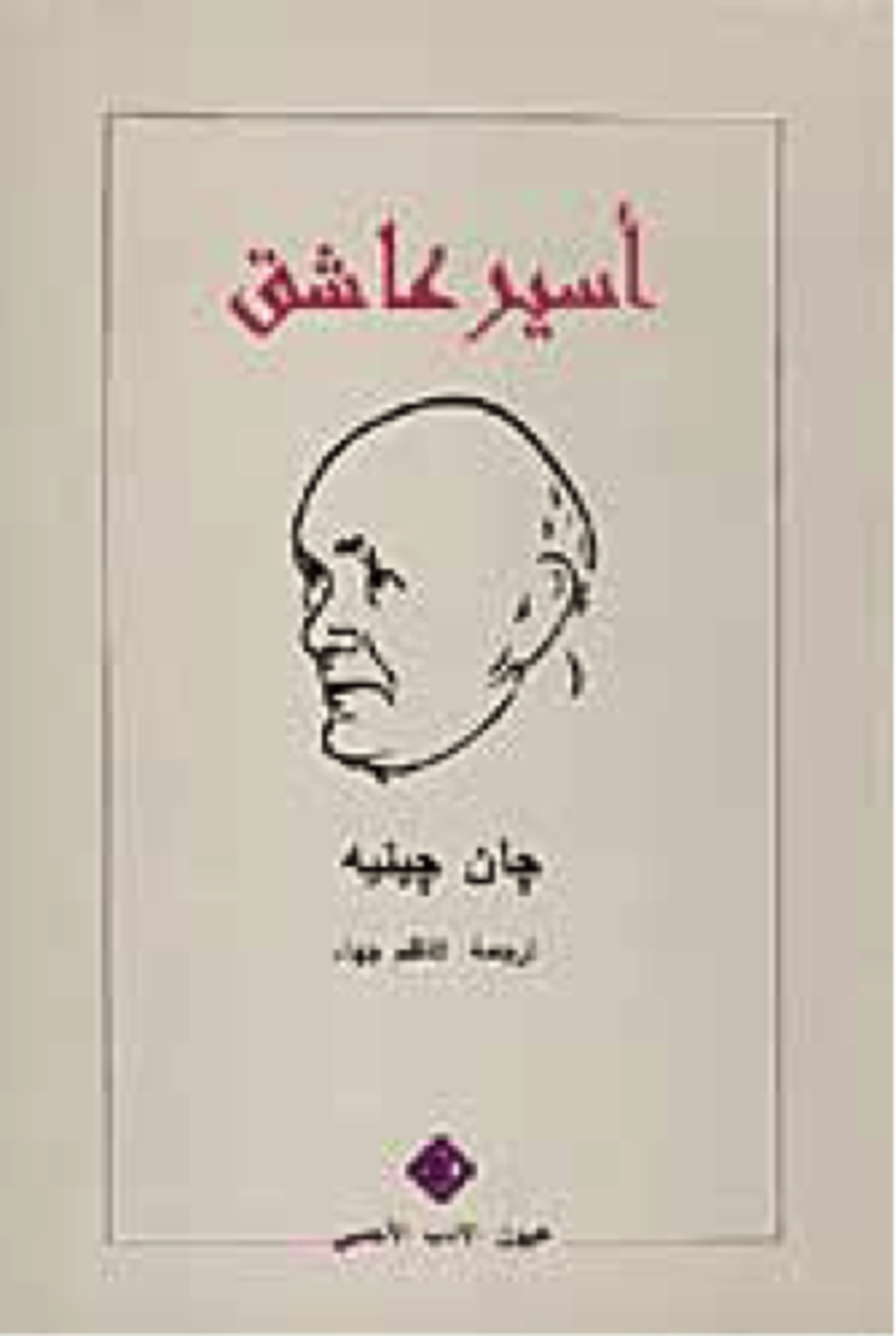

A lively archive

This account on Karameh and its specific revolutionary conjuncture offers a rich repository of ideas, debates and practices. Perhaps one of the main takeaways is best expressed in the words of Bashir Abu Maneh who, drawing on Jean Genet’s Prisoner of Love (1986), argues that “Palestinians didn’t only rise during a specific progressive global constellation but that their own conception of struggle allowed for active internationalist connections to be made with them on a human and reciprocal basis.” (16)

There is so much to say and learn about the times that preceded and followed the events at Karameh during the energizing 1960s and 1970s. Yet it is important to emphasize that this history, like some many histories, obscures and is mediated by varying forms of propaganda, romanticism, racism and hypermasculine heroism that fundamentally defined politics during this epoch. It is also an account that reproduces some categories that to a large extend have either been emptied of their meaning or lost their relevance all together.

As such it needs to urgently be reconciled with different knowledges and experiences, including those from communities that while also fighting for their existence and dignity have been marginalized for too long. Without these considerations attempts for radical change seem inevitably doom to fail.

From where I stand it seems that la lucha continua because it will never end.

In this sense, there remains a lot to do with the large available record of intellectual and collective practices of solidarity, both in terms of revisiting with fresh eyes and expanding its scope. A possibility is to approach this record not as a dead archive but rather a lively one that escapes easy categorizations and that remains committed to build oppositional spaces.

It might also be that we have to look elsewhere to find answers. There is perhaps no definitive account of a constellation for, as suggested before, stars will always appear different depending on where one stands. From where I stand it seems that la lucha continua because it will never end.

This is not meant as a way to advance an apocalyptic thesis or to argue that the fight will be a long one. Rather it is a way to problematize what seems a romantic idea. Living is a constant struggle, for some tremendously more difficult than for others. Maybe a first step forward is to avoid taking the easy way out, stay with the trouble. (17)

Notes

- (1) See Debacle in the Desert by Amir Oren.

- (2) See Israeli minister warns Palestinians of 'holocaust' by Reuters.

- (3) For a detailed account of the Battle of Karameh see Sayigh, Yezid. Armed struggle and the search for state: The Palestinian national movement, 1949-1993, Clarendon Press, 1997 and Massad, Joseph A. Colonial effects: The making of national identity in Jordan, Columbia University Press, 2012.

- (4) See interview with Golda Meir in Thames Televisions 'This week', 1970

- (5) For a great resource on the Palestinian Revolution, see learnpalestine.politics.ox.ac.uk

- (6) See for instances Fayez Sayegh (2012) 'Zionist Colonialism in Palestine (1965)', Settler Colonial Studies, 2:1, 206-225.

- (7) For a fascinating account see La tricontinentale, les peuples du tiers-monde à l'assaut du ciel by Saïd Bouamama, Syllepse, 2016.

- (8) See 1965: When Mehdi Ben Barka warned African leaders against Israel by Mohammed Jaabouk Latifa Babas.

- (9) See Spirituality by Boaventura de Sousa Santos.

- (10) See Nassar, Maha. ""My Struggle Embraces Every Struggle": Palestinians in Israel and Solidarity with Afro-Asian Liberation Movements." The Arab Studies Journal 22, no. 1 (2014): 74-101.

- (11) Thomas, Greg. "Blame It on the Sun: George Jackson and Poetry of Palestinian Resistance." Comparative American Studies An International Journal 13, no. 4 (2015): 236-253.

- (12) Lubin, Alex. Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary, UNC Press Books, 2014.

- (13) See Baeza, Cecilia. "Women in Arab-Palestinian Associations in Chile: Long Distance Nationalism and Gender Mixing." Al-Raida Journal (2011): 18-32.

- (14) See the great work on Palestinian migration by the Centro de Estudios Arabes at the University of Santiago de Chile.

- (15) Hajjat, Abdellali. "Les comités Palestine (1970-1972). Aux origines du soutien de la cause palestinienne en France." Revue d'études palestiniennes 98 (2006): 74-92.

- (16) Abu-Manneh, Bashir. The Palestinian novel: From 1948 to the present. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- (17) Some of the ideas in this last paragraph benefited from a discussion on the meanings of decolonization with Saurabh Arora.