Events of significance. An email conversation on the image contribution for rekto:verso’s Sabotage-issue

Door Arnout De Cleene, Mathew Kneebone, op Fri Dec 01 2023 23:00:00 GMT+0000In rekto:verso’s Sabotage-issue, artist Mathew Kneebone provides the image contribution. Throughout the whole issue, black fields represent power outages in San Francisco, occasionally filled with quotes from affected residents. Editor Arnout De Cleene held an email conversation with Kneebone about his research into the electric grid.

On Sept. 22, 2023, at 06:00, studio@mathewkneebone.com wrote:

Hi Arnout,

I’ve thought about how I can contribute to the magazine, continuing my research into the electric grid and its disruption (see below). I’m very interested in hearing your thoughts. I’m also happy to meet to answer questions and discuss the possibilities.

Thanks,

Mathew

Space for Downtime:

My research into the Californian grid began with Power Relations, an intervention I installed at Rib in Rotterdam from late 2021 until early 2023. The intervention included a circuit wired to Rib’s breaker panel that parsed live power outage data published online by Californian utility Pacific Gas & Electricity (PG&E). When a county serviced by PG&E experienced an inordinate amount of blackouts, the machine would simultaneously trigger a blackout at Rib.

'"Downtime" is historically used to describe a machine or system that becomes unexpectedly unavailable or offline, typically due to malfunction — including blackouts. Downtime is now often associated with idleness at the expense of productivity.'

During the intervention’s operation, I archived the outage data, which I’m researching in different ways with the help of engineer Jonathan Foote. For rekto:verso, I plan to distribute three months of outage data through the magazine as a series of black fields. The fields’ dimensions relate to the number of blackouts in San Francisco on a given day. Essentially, the publication becomes a timeline for three months of outages. Like a histogram, the height of the magazine represents the Y-axis (number of outages), with the page numbers serving as the X-axis (duration). Pages displaying these fields would include a text at the bottom, like a film subtitle, from personal messages I’ve gathered from locals experiencing those events.

For context, ‘downtime’ is historically used to describe a machine or system that becomes unexpectedly unavailable or offline, typically due to malfunction — including blackouts. Downtime is now often associated with idleness at the expense of productivity.

On Oct 3, 2023, at 13:47, arnout.decleene@rektoverso.be wrote:

Hi Mathew,

Combining excerpts from reactions to the outages as text within the black space could make for exciting combinations with the magazine articles. Trying to grasp a system by observing the moment it fails fits well with the issue in general. The effect it may have on the positioning of the articles will be radical. We must determine if and how to place all 15+ essays in the available space. I’m curious how many outages there were, i.e., how ‘black’ the issue will get and how much space remains for the essays. Readability is something we must also keep in mind, but we’re excited to figure that out.

It would be good to have a clearer picture of the impact of the diagram on the whole issue. Happy to hear your thoughts! And, also on behalf of my colleagues, thanks a lot for the terrific proposal!

Warm regards,

Arnout

On Oct. 4, 2023, at 06:42, studio@mathewkneebone.com wrote:

Hi Arnout,

'The duration of an outage is also geographic and socio-economic, with repair unsurprisingly taking longer for rural and low-income communities.'

For sure, there are practical considerations. To a large degree, the frequency of blackouts correlates with seasonal shifts in weather. Still, there’s always an element of randomness to the disruption — issues suddenly pop up due to infrastructural decay. It can depend on the location, with certain counties more affected than others. For example, massive storms hit Bay Area municipalities earlier this year, which caused significant outages. In contrast, inland communities experienced disruption at other points in the year due to heat waves and planned shutoffs to prevent failing equipment from sparking wildfires. The duration of an outage is also geographic and socio-economic, with repair unsurprisingly taking longer for rural and low-income communities.

Thanks,

Mathew

On Oct. 19, 2023, at 20:58, arnout.decleene@rektoverso.be wrote:

Hi Mathew,

I’m following up on the quotes of people affected by outages you plan to integrate into your diagrams: 'Dreams thwarted and I can't sleep', 'I see green where I live', 'They sat in the living room – exchanging nervous glances', 'Not built to withstand weather from the future', etc. These are telling in different respects. In all their concrete and anecdotal references to the specific situation the affected resident is in, they also testify to something bigger. On the one hand, the poetic nature of these utterances is striking. Perhaps in contrast to a presumption that we communicate more efficiently during an emergency (such as an outage), these quotes show the opposite: the lack of electricity unleashes poetic, figurative, comic, abstract, hermetic, and absurd language. I wonder who they are addressed to or if it’s a kind of interior monologue. They’re beautiful, that’s for sure.

On the other hand, the citations also have a more systemic aspect. These quotes were, as you wrote, posted online during an outage. There’s a paradox: how can we communicate online without electricity? All computers and smartphones depend on electricity to function. So, to communicate online, one would have to move to a non-affected place, call someone living elsewhere to communicate for you, hook up a generator, or rely on your device’s battery; probably, it’s that last option, but that’s intriguing. One way to approach it would be to see the electric system as generating excessive energy stored in batteries, making it possible to overcome the system’s failure, a kind of rudimentary backup. But, thinking about those poetic messages, I could also see it as a system that creates a lingering reservoir of energy that can be tapped into during an outage to indicate its failure in a language it — the system, the companies running the grid — is not accustomed to. As such, the blackout and the electricity used at that moment would be a kind of loophole the system creates but cannot control. I don’t know; maybe I’m reading too much into it. How do you experience the outages in your neighborhood? In any case, I think that these are, in many ways, charged messages and, as you (and PG&E) aptly name them, significant events.

All the best!

Arnout

On Oct. 24, 2023, at 22:55, studio@mathewkneebone.com wrote:

Hi Arnout,

I don’t know if brevity is unique to moments of crises so much as our communication tools and culture favor efficiency and reward impact. Our cultural response also depends on social circumstances. David Nye and other historians have written about how blackouts are liminal moments and how community responses can swing between solidarity and disorder due to, for instance, the economic climate.

Sometimes cellular internet is cut with everything else during a blackout. However, cellular towers can be outside the affected area and, therefore, still operational. It’s also common for telecommunications companies to install backup batteries or operate emergency generators near towers to ensure continuous service. But, of course, cell phones will eventually need to return to a functioning grid for recharging.

Coping mechanisms during a blackout depend on many factors, such as whether it was planned or unexpected, the scope and duration of the outage, the availability of resources, and how one can make the best of those resources. Privileged homeowners with solar panels that can store excess electricity in a battery will likely be most resilient — people who live in areas that frequently experience blackouts might already own a petrol generator. In contrast, others may improvise with available power by hacking a spare car battery or idling their car for heating or cooling or charging devices via the cigarette lighter. Some can visit a friend, family member, or community center with power. However, these options are unavailable to many others.

Electricity is a unique resource because it’s a force that needs to reach equilibrium. Batteries can store it, but when a power plant typically generates electricity, it needs to be used. How this works functionally within the grid is complex because it’s not that power plants generate electricity in the morning, and then we draw from it throughout the day. Power plants continuously generate electricity according to demand; they adjust the power output through the day based on fluctuating consumption levels. Grid operators like the California Independent System Operator (California ISO) forecast daily demands and track the load on the grid for utilities to maintain a stable electrical supply.

'I’ll walk around, talk to people if they’re willing, and take photos of the area. It’s a small window to learn and observe this communal stasis.'

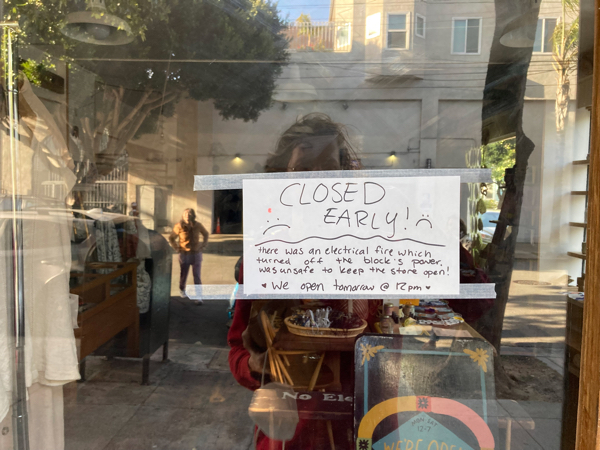

Blackouts in San Francisco typically result from a failure with the distribution equipment rather than the grid not being able to meet daily power demands. In my neighborhood, if the issue is a fallen tree over a power line, the repair team can usually fix it within an hour and a half, but that time can vary. For example, last week, contractors replaced all the utility poles on a nearby street, which caused a blackout that lasted at least a day. When my street loses power, the grocery store across from my apartment will ask customers to leave and station someone at the entrance with the automatic doors frozen open. Other businesses might close for the day and leave a handwritten notice on their window explaining the reason for early closure. Restaurant staff will hang out and chat. I’ll walk around, talk to people if they’re willing, and take photos of the area. It’s a small window to learn and observe this communal stasis.

Thanks,

Mathew

On Nov. 24, 2023, at 15:55, arnout.decleene@rektoverso.be wrote:

Hi Mathew

A few days after you last wrote, blackouts became the center of international news, as the Israeli government took out communication and internet services in Gaza, leading up to the land incursion on October 27th. It is a political aspect of blackouts, a violation of rights, with tragic consequences I hadn’t considered when writing to you earlier. It testifies to my limited knowledge on the subject and, above all, to the privileged position I’m writing you from, that I can literally write you from. When rereading our conversation, your emphasis on the geographical, sociological, and economic aspects defining the occurrence of outages, the way they are experienced, and how they are handled by those affected tie in with my new understanding of them, in a way I didn’t anticipate, with the hindsight of a situation no-one should be confronted with. It seems futile to talk about outages in the U.S., Belgium, or about a magazine. Still, I’m very grateful for your intervention in the issue, as it allows us to deepen our understanding of how we cope with a system’s failure — intentional or otherwise — and its widespread and often unnoticed effects. They are often overlooked for a reason: how can one see a situation meant to produce invisibility? How does one write, from the inside, about a situation blocking communication? The questions only multiply and intensify. Is what we term a system’s ‘failure’ really a failure, or is the system partly — malignantly? — designed to be functionally dysfunctional at times, the ‘failure’ being intrinsically part of how it functions?

All best to you in these disruptive times,

Arnout

On Nov. 27, 2023, at 15:55, studio@mathewkneebone.com wrote:

Hi Arnout,

As you suggest, failure is inherent to any technological system, whether incidental due to design flaws and degradation or deliberately through aggressive tactics, as tragically experienced by those suffering in Gaza and Ukraine. The nefarious strategy by governments to sabotage the grid to oppress civilians and conceal the effects of a crisis dates back to the 1930s, as society became increasingly reliant on electricity, and planes could travel long distances to carry out airstrikes. Nowadays, as we’re witnessing in Gaza, a country can remotely shut off power to another by flipping a switch.

Sometimes, a system’s components mask its dysfunction by design, making chronic problems invisible. For instance, while developing my intervention for Rib, I couldn’t find outage data for Treasure Island, a municipality between San Francisco and Oakland.

Treasure Island is an artificial island built for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. The Navy soon converted it into a military base during the war. In 1997, the island was rezoned for residential housing. Since then, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) has maintained the island’s power distribution system — including power lines and substation — while the Treasure Island Development Authority (TIDA) approves infrastructure upgrades. However, while other Bay Area residents can see live blackout information via an online outage map, neither SFPUC or TIDA publicly discloses real-time power outage data for Treasure Island.

'Sometimes, a system’s components mask its dysfunction by design, making chronic problems invisible.'

I recently interviewed Barklee Sanders, a Treasure Island resident advocating upgrading the island’s antiquated infrastructure. During our conversation, he highlighted the challenges faced by his community, which happens to be the second poorest zip code in California, with over 60% of its population consisting of people of color, homeless individuals, aged-out youth, and other marginalized groups. Treasure Island experiences blackouts approximately four times more frequently than other Bay Area communities. Until recently, its power lines were connected in series, meaning a disruption on one wire could affect the entire island and leave all residents in the dark.

Luxury condos were recently constructed on Treasure Island and neighboring Yerba Buena Island — a natural hilly island attached to Treasure Island. Initially, these condos were connected to the same power lines as Treasure Island residents and, therefore, shared the same blackouts. To stabilize the condo’s electricity, TIDA swiftly approved a new power line that bypassed Treasure Island’s long standing inhabitants. It split the two communities in half, electrically redlining existing residents.

'We sometimes use the term "blackout" to refer to amnesia. People who experience infrequent power loss tend to forget these moments once the lights turn on again.'

We sometimes use the term ‘blackout’ to refer to amnesia. People who experience infrequent power loss tend to forget these moments once the lights turn on again. However, for Treasure Island residents, blackouts are chronic. With TIDA and the SFPUC unwilling to publish live power outage data, the community and its ongoing infrastructural issues remain invisible. This only further entrenches the problem by making it appear that it doesn’t exist. Barklee concluded the interview by stating that SFPUC and TIDA won’t improve the island’s dilapidated infrastructure because those in charge live elsewhere and don’t experience the same problems. There’s malignancy to this indifference.

Thanks,

Mathew

Mathew Kneebone’s research into the Californian grid began with Power Relations, an intervention at Rib in Rotterdam from late 2021 until early 2023. Rib supports ‘Power Relations’ as part of its ongoing public exhibition program ‘The Last Terminal: Reflections on the Coming Apocalypse’. / (Slash) in San Francisco hosted an iteration of the intervention in early 2023. Currently, Rib's director, Maziar Afrassiabi, and Mathew Kneebone are working together by inviting other art institutions to integrate the work into their infrastructure.